Oct. 8 2017. I’ve been on the road for a week now searching for lost crops. It’s pouring rain into the misty Red River Gorge, and I’m holed up at the lovely Daniel Boone Coffee Shop, so now is a good time to record some reflections so far.

I started my journey in Pittsburgh, where the Monongahela River and the Allegheny River join to form the Ohio River. This was a fitting place to begin, since the Ohio River was one of the great thoroughfares of pre-Columbian North America. I study a group of lost crops that were cultivated for thousands of years in a vast mid-continental region defined by its river valleys: the Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi rivers, among many others. Think of the Ohio as an ancient high road, connecting the heart of the midcontinent to the northeast via the Appalachian Mountains. I left the analogous modern high road, Route 70, in Wheeling, WV, and turned south to follow Route 7 along the upper Ohio River. When I hopped out of my car for the first time, I was looking for three floodplain weeds that were once important crops: native goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri), sumpweed (Iva annua), and erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum).

Route 7 along the upper Ohio River.

I spent a fruitless but sun-drench and beautiful afternoon walking the Ohio River valley between Wheeling, West Virginia and Marietta, Ohio. I mostly prospected around small oil wells in the floodplain that looked like something out of another century. The clearings and networks of trails connecting them were ideal places for the weedy species I was looking for, and they were out of the way enough that they weren’t overrun with invasive species. The next morning, I spent a few hours circumnavigating Middle Island, an island in the Ohio River that was one farm land but is now managed as a wildlife refuge. I came up empty handed in all of these likely locations, and in the afternoon decided to abandon the floodplain for now and head up onto the Allegheny Plateau.

Clearing around oil wells are good places to look for lost crops, or get electrocuted by DIY wiring!

If you’re from a coast, you may think of the entire region where I work as fly-over country, an endless expanse of corn fields, but it is actually a very diverse landscape. The upper Ohio valley cuts southwest through its mountainous eastern margin. Some of the key archaeological evidence for the lost crops came from caves and rockshelters along the western Appalachian front, stretching from Ohio to Tennessee. From the millions of crop seeds recovered from caves and rockshelters in this upland region, we know that the lost crops were cultivated here beginning in the end of the Late Archaic period, about 3500 years ago. The three lost crops that I am looking for on this trip are all species of disturbed areas, usually near water, so their presence in mountain caves is somewhat surprising. I think that we can deduce that people made space for them outside of their natural habitat, by clearing forested terraces in mountain valleys and cultivating them there. Given this history, I was curious to see where these species would occur in the uplands without the major assist they once received from ancient farmers.

Ash Cave, Ohio. An enormous cache of ancient crop seeds, including domesticated native goosefoot (similar to quinoa) was recovered here, far from the natural habitat of a floodplain weed.

In Athens, I joined forces with my colleague Paul Patton, a professor at Ohio University. After a brief consultation with the archaeologists and botanists at the Wayne National Forest headquarters, we started prospecting along dirt roads near Monday Creek, a small tributary of the Hocking River. After several hours of not finding lost crops, we had started to get a little careless, strolling along and chatting with our eyes trained on the strips of weeds between the road and the forest. This gave us plenty of time to compare notes. “There’s no sumpweed up here” Paul told me. “But, the USDA map…” I began, but he was one step ahead of me. The Wayne National Forest is his study area, and he’s excavated several Archaic and Woodland sites in those hills. “The occurrence you saw in Athens County was mined from one of my papers – it’s from an archaeological site, not a modern occurrence.”

USDA Map showing sumpweed (Iva annua) occurrences. You can see that Athens County is marked in green, meaning that Iva annua has been collected in that county. Turns out, though, that accession was from archaeological specimens excavated by Paul, not living plants. If you know the major rivers in the region, you might notice that the counties with sumpweed are mainly located along them, not up in the hills and mountains.

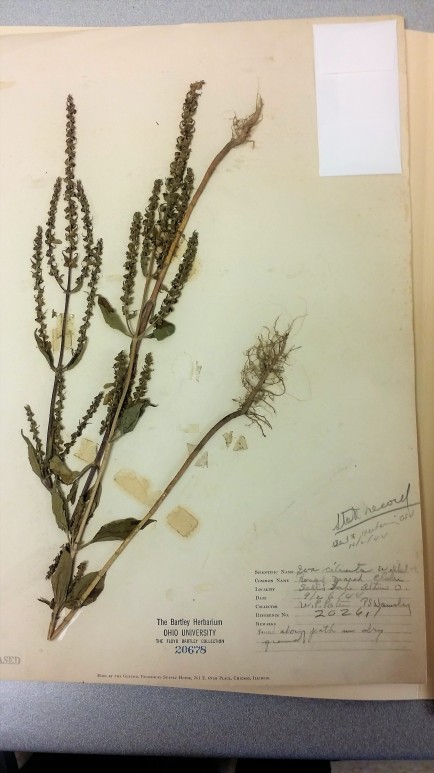

For hundreds of years, botanists have been collecting plants, identifying them, and depositing their pressed specimens in curious institutions called herbaria (singular: herbarium). These collections are a priceless record of plant distributions over time, but they are also idiosyncratic. Coverage may be very good within a 50 mile radius of some avid 19th century botanist’s house, but non-existent the next county over. Still, based on the data I’ve personally amassed from herbarium specimens, plus the considerably bigger databases of the USDA and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), there isn’t (and hasn’t been for at least two hundred years) any sumpweed up in the hills where we were looking.

A sumpweed specimen we examined at the Ohio University herbarium from Athens, near the Hocking River. We checked this location, but it is long gone.

After this revelation, I was very surprised when Paul suddenly stopped in his tracks – “Is that?!” Following his shocked gaze, I realized that what it was: a patch of sumpweed plants growing along a parched dirt road running uphill from an old mine – a strange place for a plant that is basically a wetland species. We both stood around not believing our eyes while we texted a picture to our friend Liz, who has been cultivating sumpweed for the past three years. When she texted back “Cute!” rather than “You’re idiots that isn’t sumpweed,” we gleefully started collecting seed, data, and herbarium specimens from our first lost crop find of 2017.

This populations is growing literally a stone’s throw from ancient sites where it was an important crop. It’s been hundreds of years since then – hundreds of years during which this site was clear cut, then mined for coal and oil, then reforested. Could this be a remnant of a cultivated population? It would take A LOT more data on where sumpweed does and does not occur to answer that question. Actually that’s part of what brought me down to Boone National Forest, where I’m currently getting rained on. Like the Hocking River and its tributaries, the Red River has provided plenty of evidence for the cultivation of lost crops in the highlands. The lost crops aren’t supposed to be here either, but you never know what you might find when your start looking.

Collecting goosefoot seeds along the Hocking River with Paul.

Post Script, Morning of Oct. 9

I rallied from my warm dry retreat at the Daniel Boone Coffee Shop and headed down into the Red River Gorge minutes after finishing this post. To get into the gorge, you first have to pass through the spectacular Nada Tunnel, which was created in the early 20th century to transport lumber out of what was then still an old growth forest. After passing through, the road dives down into the gorge. Route 613, still a pot-holed dirt track in some places but worth the effort, winds its way down the bottom of the gorge along the Red River, past several caves and rockshelters that are famous (at least, to me) for their contributions to our knowledge of the lost crops.

Nada Tunnel, entrance to Red River Gorge, Kentucky.

As I trudged along one roadside between campsites in the pouring rain, my eyes alighted on a form that I know from my dreams and nightmares – little erect knotweed, the elusive subject of recently completed dissertation – my lost crop. This plant is extremely rare: in four years of searching this is only the sixth population I have ever found. But since I’ve been growing it for going on three years now, I can spot it anywhere, even if it is mowed and bedraggled, like these ones. Back in my car, I checked the location on my big map of Kentucky. I was directly below Courthouse Rockshelter– the very location where excavations had yielded 2,000 year old caches of erect knotweed and other lost crops back in 1998. It was getting dark and didn’t have time to investigate further, but I am headed back up into the hills now!

Erect knotweed growing along the Red River, just below Courthouse Rockshelter.

Pingback: ‘Life finds a way’ in the ruins | Natalie G. Mueller

Pingback: Hunting for the ancient lost farms of North America - Grouvy Today

Pingback: Hunting for the ancient lost farms of North America | abskillz.com

Hello, Nadia –

Nice to know that these days someone can live my dream. I started collecting weeds in college (Dayton, Ohio) 40 years ago, but was too poor to try making a living at it during the Reagan Recession. I read about you on Ars Technica and will keep an eye on your blog to see what you find — and hope to try growing some of your favorites on my own 4 acres in the Virginia Piedmont. Good hunting!

LikeLike

Wow, totally amazing!

LikeLike

Pingback: Hunting for the ancient lost farms of North America | The Repatriation Files